Why Your Race Affect College Admissions

How many minorities does it take to achieve school diversity?

Promotional image for the 2021 Marvel movie Eternals

With affirmative action likely to be obliterated next summer, emotions are running pretty high, with some celebrating the end of what seemed like an unfairly discriminatory measure that punished certain people (Asians) for their success and others lamenting that the loss of diversity would be a devastating blow to students of all races.

Now, however, this most recent lawsuit by Students For Fair Admissions (SFFA) against Harvard and the University of North Carolina has forced Harvard to relinquish precious admissions data that does in fact show a pattern of blatant bias against Asian applicants.

Not that this is unexpected or anything; we’ve all known this since long ago even when there was never any clear evidence because Ivy League admissions practices and statistics were kept extremely confidential.

Naturally, this raises all sorts of questions. What exactly is the process by which Harvard weeds out the Asians? How did they get away with this for as long as they did? Why did it take all the way until now for something to be done about this? Will this finally fix everything and make it easier for Asians to get into their dream schools?

Because the heart of this issue lies with race, we must first take a glance at America’s historical relationship with its minorities before we can begin to understand what’s really going on and what’s at stake here.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

Working with a civil rights organization called the NAACP (The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), Oliver Brown, an African-American welder in Kansas, challenged the “separate but equal” policy of segregation by attempting to enroll his daughter Linda in the nearby white school so she wouldn’t have to go to the black school to which she had been assigned that was an additional mile away.

When she was denied enrollment, her father Oliver, along with others in a coordinated effort, sued the Topeka board of education. When this case went to the Supreme Court, two major factors swayed the decision:

First, a psychological study was submitted to demonstrate how segregation can internalize self-hatred. In the experiment, African-American children were presented with a white doll with blond hair and a brown doll with black hair before being asked various questions like which doll they would play with, which one is the nice doll, and which one looks bad. A clear majority of black children preferred the white dolls.

The Court decided that even if white facilities were exactly the same as colored facilities in every aspect, the mere act of segregation was deeply problematic:

To separate [black children] from others of similar age and qualifications solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely to ever be undone.

To this day, the doll test remains just as relevant. Why do these sentiments continue to persist even long after segregation has been banned? For starters, just look at the skin tones of the people in advertisements and the heroines in shows and movies.

Look at this screenshot I took:

This is literally the first thing I saw when I went to the website for Sogo Taiwan (you know, the Japanese department store chain located in Taiwan, whose population is 95+% ethnically Han Chinese). So why would they choose to use an all-white family in an advertisement for an Asian business in an Asian country filled with Asian people? I’ll leave you to ponder the answer to that, but know that when we’re constantly bombarded by such imagery, we are very much conditioned to think that lighter skin is the standard of beauty, of goodness, that white is right.

Second, and even more influential, the US was in the midst of the Cold War during this time, and Soviet Russia was gleefully pointing out what hypocritical nonsense American democracy was because of how Americans treated black people, giving birth to the infamous whataboutism “And you are lynching Negroes.”

Any criticisms that Americans had of any other country would basically just be met with, “Yeah well you guys are assholes towards black ppl so stfu.” This was an incredibly effective attack that was employed far beyond Russia’s borders because people all over the world understood that if Americans are okay with treating one minority poorly, then there’s no reason they wouldn’t treat any other non-white person equally poorly.

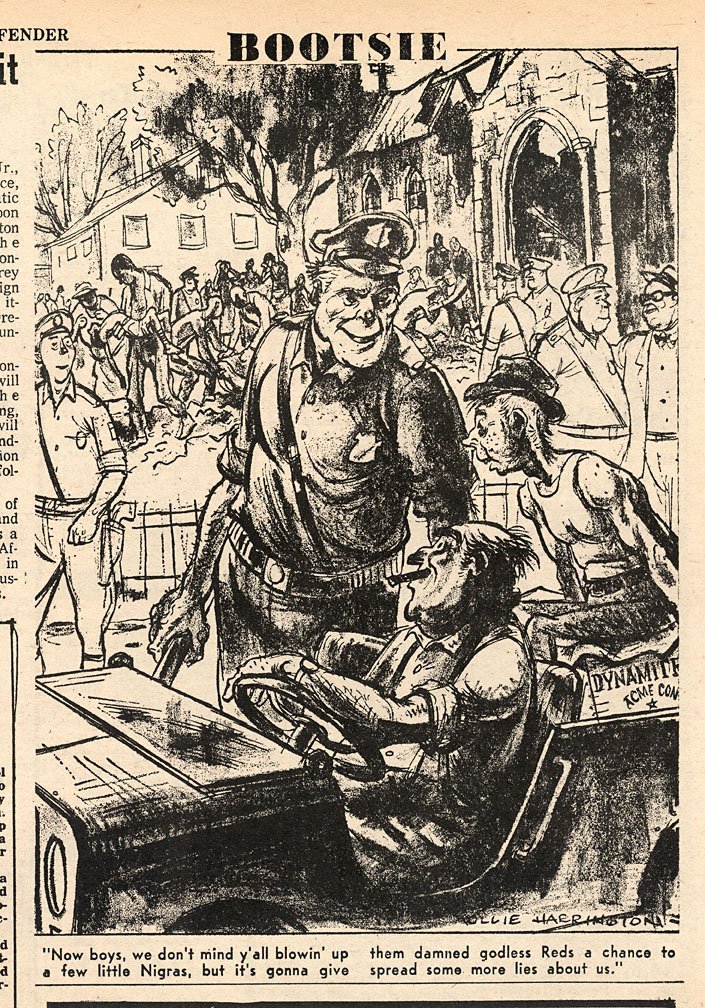

This cartoon references the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing of 1963, in which white supremacist terrorists planted nineteen sticks of dynamite beneath the steps of a black church in Alabama, killing four black girls and wounding dozens more.

This enormously significant incident brought to national attention the fact that the evils of racism were still very much alive in America and didn’t magically go away just because slavery was outlawed a century ago. As one white lawyer said to his audience in a speech, "Who did it? We all did it...every person in this community who has in any way contributed...to the popularity of hatred is at least as guilty...as the demented fool who threw that bomb.”

“The shame of America” (1968) by Soviet poster artist Viktor Koretsky

The presidential administration was so alarmed by this situation that they even wrote a plea to the court. They were less worried about securing equal rights for non-whites and far more upset about how they were being utterly humiliated on the international stage:

The United States is under constant attack in the foreign press, over the foreign radio, and in such international bodies as the United Nations because of various practices of discrimination in this country. . . . Soviet spokesmen regularly exploit this situation in propaganda against the United States. . . . The hostile reaction among normally friendly peoples . . . is growing in alarming proportions. . . . [T]he continuance of racial discrimination in the United States remains a source of constant embarrassment to this Government in the day-to-day conduct of its foreign relations; and it jeopardizes the effective maintenance of our moral leadership of the free and democratic nations of the world.

In the end, the Court ruled in favor of Brown:

📜 We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of "separate but equal" has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. Therefore, we hold that the plaintiffs and others similarly situated for whom the actions have been brought are, by reason of the segregation complained of, deprived of the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment states that “no State shall ... deny to any person ... the equal protection of the laws.” In other words, individuals in similar situations must be treated equally by the law. Remember this. It’s important because it comes up again and again in future affirmative action cases.

As you already know, just because something becomes law doesn’t mean people automatically obey. There was plenty of hostility from Southerners who refused to desegregate their schools.

The infamous Little Rock crisis of 1957 in which the governor of Arkansas tried to stop nine black girls from entering Little Rock Central High School by calling in the state national guard until President Dwight D. Eisenhower took over and called in the US Army to escort the students safely through the angry white mob.

An iconic photo of Hazel Bryan shouting at Elizabeth Eckford. Some of the things Hazel shouted included, “Two, four, six, eight! We don’t want to integrate!” and “Go home, nigger! Go back to Africa!” Amazingly, Hazel ended up having an incredible redemption arc and became not only friends with Elizabeth but also a civil rights activist.

The "Stand in the Schoolhouse Door" incident of 1963 in which the Governor of Alabama, whose slogan was "segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever," stood in front of a school entrance to block two black students from entering until President John F. Kennedy ordered the state national guard to remove him.

To help enforce desegregation policies, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed which prohibits racial segregation in schools and public accommodations, unequal application of voter registration requirements, and employment discrimination. Title VI of this act specifically prohibits “discrimination under federally assisted programs on ground of race, color or national origin” to reinforce the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause mentioned earlier, so you’ll see this come up repeatedly as well.

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978)

Just because integration is now a thing doesn’t mean minorities are suddenly propelled to a level playing field when they’ve been historically denied access to proper facilities and resources in America since forever, so UC Davis, whose students were still all white, decided to adopt a special admissions policy (a.k.a. affirmative action) by reserving 16 out of every 100 spots for qualified minorities.

Enter Allan Bakke: a white male with strong academics who served as a Marine for four years, served in Vietnam, achieved the rank of captain, and worked as an engineer at NASA. With extracurriculars like that you’d think he’d get into all the medical schools he later applied for, but unfortunately, in those days medical schools openly practiced age discrimination, and Bakke was 33 years old. And so, his application was rejected from all the dozen-plus places he applied to, but he was especially annoyed by UC Davis’s special admissions program that admitted minorities whose academic scores were lower than his. Sound familiar?

Allan Bakke (bah-key)

Lodging his complaints with the admissions committee, Bakke spoke to UC Davis’s assistant dean who recommended that he reapply because he had been so close and, ironically, even recommended a couple lawyers interested in the issue of affirmative action for Bakke to contact if his application was rejected a second time.

Bakke applied to UC Davis again the next year. Once again, he was rejected and naturally got in touch with those recommended lawyers to sue the school. Predictably, the assistant dean, who remarked afterwards that he “simply gave Allan the response you'd give an irate customer, to try and cool his anger” and maintained that he never expected Bakke to actually sue, was subsequently demoted and fired.

The nine Supreme Court justices (eight of whom were white) were divided in their opinions and could not reach a unanimous decision on the question of affirmative action itself. Ultimately, they ruled that UC Davis’s practice of reserving seats was a strict quota that violated the Equal Protection Clause. However, they still couldn’t reach a unanimous decision on the question of affirmative action itself.

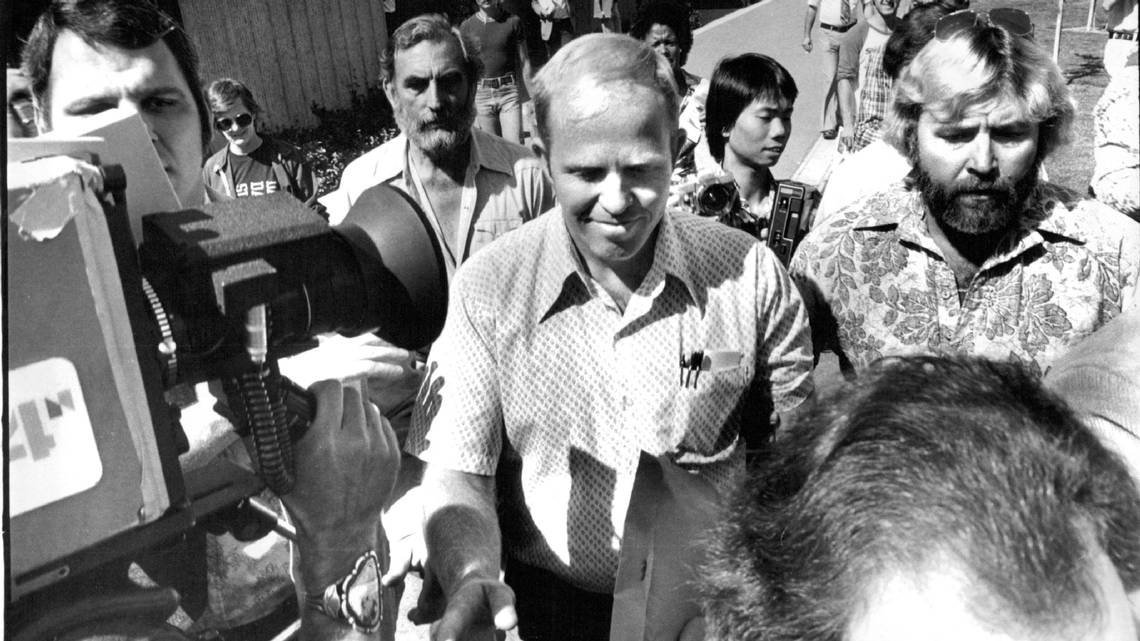

Bakke with plainclothes security escorting him to his first day of class at UC Davis Medical School

Justice Thurgood Marshall, the only African-American on the court, summarized the issue well:

📜 The decision in this case depends on whether you consider the action of the Regents as admitting certain students or as excluding certain other students. If you view the program as admitting qualified students who, because of this Nation's sorry history of racial discrimination, have academic records that prevent them from effectively competing for medical school, then this is affirmative action to remove the vestiges of slavery and state imposed segregation by ‘root and branch.’ If you view the program as excluding students, it is a program of ‘quotas’ which violates the principle that the ‘Constitution is color-blind.’”If giving one student an advantage creates a disadvantage for another, what is to be done? Even if we help someone who needs it, is it fair to sacrifice another who isn’t even responsible for creating the conditions that necessitate affirmative action in the first place? As Justice Lewis F. Powell noted, “There is a measure of inequity in forcing innocent persons [like Bakke] to bear the burdens of redressing grievances not of their making.”

But the really important thing Justice Powell wrote was this:

📜 “[In] order to justify the use of a suspect classification [i.e. in order to discriminate on the basis of race], a State must show that its purpose . . . is both constitutionally permissible and substantial, and that its use of the classification is ‘necessary . . . to the accomplishment’ of its purpose. […] [R]ace or ethnic background may be deemed a ‘plus’ in a particular applicant’s file, yet it does not insulate the individual from comparison with all other candidates for the available seats. The file of a particular black applicant may be examined for his potential contribution to diversity without the factor of race being decisive.”This was huge because it established that affirmative action policies are actually acceptable so long as they meet these two essential criteria:

The policy has to work towards a meaningful goal and can’t just exclude certain groups of people for no good reason

Race can be a factor in admissions, but it can’t be the factor that makes or breaks applicants, and they must be compared on an individual basis against other candidates (what is referred to as “narrowly tailored”)

Bakke with his wife and child at his graduation ceremony which you can watch a clip of here

The court ruled against UC Davis because (1) there was no evidence showing that educating more minority doctors instead of white ones had anything to do with the school’s purported goal of “increasing the number of physicians who will practice in communities currently underserved” and (2) quotas indisputably turned race into the sole deciding factor that automatically disqualified specific groups and thus counted as reverse discrimination.

Nonetheless, the fact that this case was decided by a plurality opinion rather than a unanimous decision and the lingering ambiguity of what exactly was and wasn’t allowed would set the stage for the many challenges of affirmative action to come.

Hundreds of student, labor, and civil rights groups gathered at UC Berkeley to protest the Bakke decision

As though UC Davis hadn’t taken enough L’s, the school then refused to pay for Bakke’s legal fees, so Bakke took them to court again and was eventually awarded $183,089 which, adjusting for inflation, would be a little over $700,000 USD today.

Gratz v. Bollinger & Grutter v. Bollinger (2003)

Jennifer Gratz, Barbara Grutter, and several other students—all white—sued the University of Michigan, whose president at the time was Lee Bollinger, when they were denied admission while minority students with lower academics were accepted, alleging that their rights had been violated under the Equal Protection Clause and Title VI.

Gratz applied to UMich’s College of Literature, Science, and the Arts (LSA) which, back then, used a 150-point scale to rank applicants, with 100 points guaranteeing admission. Here’s what their scoring system looked like (source):

Note that a perfect SAT/ACT score is worth 12 points, an “outstanding essay” only 1 point (they had to write three essays, so they could get up to 3 points), and being an “underrepresented racial/ethnic minority” a whopping 20 points.

To understand how powerful that boost is, consider a white student and a black student who both have a perfect 4.0 GPA. The black student would be automatically admitted without having to do anything else while the white student wouldn’t be guaranteed admission even with a perfect SAT score.

Or in an example of what might be considered a “minimally qualified” applicant, a black student (+20) who is a resident of Michigan (+10) in an underrepresented county (+6) would only need to get a 1050 on the SAT (+10) and a 2.7 GPA (+54) to get in without having to do any extracurriculars whatsoever. For reference, in 2003, UMich was ranked as the 25th top university (the same rank as it has right now, actually) tied with UCLA and as a top 10 law school along with UC Berkeley and UPenn.

So notice what’s happening here. Because of Bakke, schools can’t just use quotas to guarantee that they’ll have a minimum number of minority students. Thus, UMich (and other top schools at the time) created a scoring system that enables certain races to receive a boost to work towards that same goal of ensuring they’ll get a desired population of underrepresented minorities.

So is a scoring system like this constitutional? After all, the system looks at other factors besides race, and the point boost doesn’t automatically guarantee admission on its own like UC Davis’s reserved seats did.

Here’s an excerpt of the Supreme Court grilling UMich’s attorney, civil rights lawyer John Payton, on the school’s points system. Remember from the Bakke decision that in order for something like this to be legal, it must judge applicants on an individual basis instead of simply generalizing by race.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: I have to say that in -- in looking at your program, it looks to me like this is just a -- a disguised quota. You have a -- a minority student who works very, very hard, very proud of his athletics, he gets the same number of points as a minority person who doesn't have any athletics -- that to me looks like an overt quota.MR. PAYTON: Here's how our system works and I believe it's not a quota at all and I can believe -- I can simply explain this. The way it works, an application comes in, it is reviewed on the basis -- every single application is read in its entirety by a counselor, every single application. It is in fact judged on the basis of the selection index, which has the 20 points for race and 20 points for athletics, but it also has all sorts of other things that it values, in state, underrepresented state, underrepresented county within Michigan, socioeconomic status, what your school is like, what the curriculum that you took at your school is like.JUSTICE SCALIA: But none of that matters.MR. PAYTON: Your grades --JUSTICE SCALIA: None of that matters if you're minimally qualified and you're one of the minority races that gets the 20 points, you're in, correct? The rest is really irrelevant?MR. PAYTON: The way it works is that every application comes through and it's read in its entirety, it is evaluated taking all of these factors into account, and then based upon the number that comes off the selection index which can go up to 150, the students are all competing against each other. There is a score that is evaluated throughout the year, because there's an overenrollment problem that always has to be managed and if the score is higher, you are in, and that doesn't matter about anything other than what the score is. In addition, the counselor can on the basis of three factors see that an application is reviewed by the admissions review committee.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: Mr. Payton, in your brief, you say the volume of applications and the presentation of applicant information may get impractical for LSA to use admissions system as the much smaller University of Michigan Law School.Now, you're saying that every single application for admission to LSA is read individually?MR. PAYTON: Yes. Sometimes twice. Because every application is read when it comes in, and those that a counselor flags that -- because they find that there's three factors you have to have flag an application -- academically able to do the work, above a certain selection index score and also contributes at least one of various factors that we want to see in our student body, including underrepresented minority status, but also very high class rank and a whole range of other things.

The first major problem pointed out by Justice Kennedy is that because applicants are only allowed one miscellaneous bonus on the sheet (yup, go back and check the fine print!), other notable factors are not taken into account.

In other words, a black student who comes from a poor family and is an exceptional athlete would, instead of getting 60 points, still be considered the same as a black student who has neither of those additional considerations. Thus, they are no longer being judged on an individual basis because all black people are just worth the same 20 points in that category.

Check how Payton defends against a similar example posited by Justice Breyer:

JUSTICE BREYER: I wanted to go back to Justice Kennedy's question. The point system here, does it meet the opinion of Justice Powell in Bakke when that was called for individualized consideration? Now, the concern that it does not, is that you under this system would seem to have the possibility that two students -- one is a minority, African American, one is not, majority, and they seem academically approximately the same and now we give the black student 20 points and the white student, let's say, is from the poorest family around and is also a great athlete, and he just can't overcome that 20 points -- the best he can do is tie. And so that's the argument that this is not individualized consideration.And I want to be sure I know what your response is to that argument.MR. PAYTON: I have two responses. The first is to say that it is individualized if that white student actually was socioeconomically disadvantaged, that could be taken into account.JUSTICE BREYER: But remember he has that and gets 20 points for it?MR. PAYTON: Yes.JUSTICE BREYER: And he also is a great athlete and I've constructed this example to make it difficult for you, and -- but I mean you see he can only get 20 points, no matter how poor he is. And no matter how great an athlete he is as well, and the -- let's say the black student who has neither ties him?MR. PAYTON: Yes.JUSTICE BREYER: But on individualized consideration, the black student might lose, if there were the individualized consideration.MR. PAYTON: Well, he might --JUSTICE BREYER: And that's -- and that's what you're giving him. Now what is the answer I'm -- I'm trying to find your answer?MR. PAYTON: The answer is we value both of those aspects of diversity. We want both of those represented in our student body, all right, if they tie, they will be judged exactly the same as far as how the selection index worksJUSTICE KENNEDY: What you're saying is that race is individualized consideration?MR. PAYTON: I'm saying that each student --JUSTICE KENNEDY: Otherwise you're saying that only in the hypothetical given that only the white student receives individualized consideration?MR. PAYTON: No, no. They both --JUSTICE KENNEDY: Some are more equal than others?MR. PAYTON: They both receive individualized consideration. They're both reviewed in their totality. They both may be sent to the admissions review committee where they get a second reading. In Bakke --JUSTICE BREYER: If in those circumstances, because we have the white student who is both a good athlete and also very poor, and the other student, the minority is not, could that be sent to the -- the individual -- could that be sent to the review committee and the review committee would say, well, we have a special circumstance here, and even though the points tie, nonetheless when we look at it carefully, we see that the white student has these extra pluses, despite the points, we let in the white student?MR. PAYTON: The admissions review committee -- about 70 percent of the applications that it reviews in any given year are white student applications that are sent to it. Okay. It can reach its judgment irrespective of whatever happened in the selection index score.JUSTICE BREYER: So they can ignore the points?MR. PAYTON: They can -- actually once it goes to them they simply look at the application and make a judgment.JUSTICE BREYER: So I want a clear answer to this. That review committee can look at the applications individually and ignore the points?MR. PAYTON: It does.JUSTICE BREYER: Yes. The answer is yes?MR. PAYTON: The answer is yes.JUSTICE BREYER: O.K.

The second major problem here is more subtle. Although Payton contends that applications can be submitted to an admissions committee for further review, the issue lies in these qualifications that the app could or may or might be reviewed. While the review process is indeed properly narrowly tailored (individualized), the issue is that not every applicant is given this level of personalized attention. The vast majority of applications are still decided by that initial scoring system, and only special cases that have been flagged receive special scrutiny.

This is quite different from the admissions policy of UMich’s Law School to which Grutter applied. The law school assigned students an index score as well but it was based solely on their UGPA (undergraduate GPA) and LSAT (Law School Admission Test—unrelated to Collegeboard). More importantly, each application was considered holistically, taking everything about the student into consideration, as you can see in their policy here:

When the differences in index scores are small, we believe it is important to weigh as best we can not just the index but also such file characteristics as the enthusiasm of recommenders, the quality of the undergraduate institution, the quality of the applicant’s essay, and the areas and difficulty of undergraduate course selection. These “soft” variables not only bear on the applicant’s likely graded performance but also have the additional benefit that they may tell us something about the applicant’s likely contributions to the intellectual and social life of the institution. Thus an applicant who has performed well in advanced courses in a demanding subject may have more to offer both faculty and students than an applicant with a similarly high average achieved without ever pursuing in depth any area of learning. Other information in an applicant’s file may add nothing about the applicant’s likely LGPA [law school GPA] beyond what may be discerned from the index, but it may suggest that that applicant has a perspective or experiences that will contribute to the diverse student body that we hope to assemble. The applicant may for example be a member of a minority group whose experiences are likely to be different from those of most students, may be likely to make a unique contribution to the bar, or may have had a successful career as a concert pianist or may speak five languages.

This key difference is why the court voted 6-3 to rule in favor of Gratz, striking down the school’s point system, but ultimately voted 5-4 against Grutter to uphold affirmative action as a whole. Justice O’Connor explains the different circumstances here thusly:

📜 The law school considers the various diversity qualifications of each applicant, including race, on a case-by-case basis. By contrast, the Office of Undergraduate Admissions relies on the selection index to assign every underrepresented minority applicant the same, automatic 20-point bonus without consideration of the particular background, experiences, or qualities of each individual applicant. And this mechanized selection index score, by and large, automatically determines the admissions decision for each applicant. The selection index thus precludes admissions counselors from conducting the type of individualized consideration the Court's opinion in Grutter requires: consideration of each applicant's individualized qualifications, including the contribution each individual's race or ethnic identity will make to the diversity of the student body, taking into account diversity within and among all racial and ethnic groups.

Okay, so the law school fulfilled the narrowly tailored condition of affirmative action. But don’t forget the other essential condition: working towards a meaningful goal. What exactly does that even mean?

That “meaningful goal” would come to be defined in this case as critical mass. The phrase “critical mass” tends to conjure images of nuclear reactors swelling and shaking while sirens blare and a female voice calmly instructs everyone to exit as soon as possible before the whole place blows, but all it really means is just a sort of threshold or tipping point until something starts to happen.

This 1989 headbanger, for example, accurately prophesized that our unchecked destruction of nature had reached critical mass and would set us down the path of our own annihilation.

It’s not all necessarily negative, though. Payton explains how critical mass works in the context of affirmative action:

MR. PAYTON: Michigan is a very segregated State. Detroit is overwhelmingly black. Its suburbs and the rest of the state are overwhelmingly white. While Michigan is extreme in this regard, it's not that extreme from the rest of the country. The University's entering students come from these settings and have rarely had experiences across racial or ethnic lines. That's true for our white students. It's true for our minority students.They've not lived together. They've not played together. They've certainly not gone to school together.The result is often that these students come to college not knowing about individuals of different races and ethnicities. And often not even being aware of the full extent of their lack of knowledge. This gap allows stereotypes to come into existence.Ann Arbor is a residential campus, just about every single entering student lives on campus in a dorm. On campus, these 18-year olds interact with students very different from themselves in all sorts of ways, not just race, not just ethnicity, but in all sorts of ways. Students, I think as we know, learn a tremendous amount from each other.Their education is much more than the classroom. It's in the dorm, it's in the dining halls, it's in the coffee houses. It's in the daytime, it's in the nighttime. It's all the time.Here's how critical mass works in these circumstances. If there are too few African American students, to take that same example, there's a risk that those students will feel that they have to represent their group, their race. This comes from isolation and it's well understood by educators. It results in these token students not feeling completely comfortable expressing their individuality.On the other hand, if there are meaningful numbers of African American students, this sense of isolation dissipates.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: Mr. Payton, what is a meaningful number?MR. PAYTON: It's what we've been referring to as critical mass.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: What is critical mass?MR. PAYTON: Critical mass is when you have enough of those students so they feel comfortable acting as individuals.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: How do you know that?MR. PAYTON: I think you know it, because as educators, the educators see it in the students that come before them, they see it on the campus.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: Do they -- professors at the University of Michigan spend a lot of time with the students?MR. PAYTON: Yes, they do. This is an incredibly vibrant and complex campus that has diversity in every conceivable way. And I think --CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: Do they spend a lot of time with them other than lecturing to them?MR. PAYTON: They do. In the record, we actually have an expert report that's not contradicted in any way by Professor Raudenbush and by Professor Gurin, just on the issue of how do you know when you have enough students in different contexts and circumstances that there will be these meaningful numbers.CHIEF JUSTICE REHNQUIST: What do they say?MR. PAYTON: They said that given the numbers that have been coming through in the last several years, we are just getting to that critical mass. And the way they analyzed it was to look at the circumstances in which students interact. Entering seminar, a dorm context, a student activities context, student newspaper context, to see what would happen if you distribute the students across these small encounter opportunities.

If this sounds strange, you might be surprised to realize that this is something you already understand intuitively. Suppose that Princeton University had 3000 students, all of whom are Chinese with perfect GPAs and perfect SAT scores. Do you think the learning environment in such a school would be identical to if it had a diverse mix of other ethnicities? In which environment do you think you would encounter a greater variety of cultures and ideas? In which environment would you prefer to learn?

Even beside the fact that the benefits of diversity have been scientifically proven, you already know in your gut that there is something inherently beneficial about stepping outside of an echo chamber and immersing yourself in a new environment. That’s a huge part of why international students want to study in America, isn’t it? It’s not about the student-to-teacher ratios or the number of Nobel Prizes the professors have won; it’s about the diverse experiences you’ve come to expect in the melting pot that is America.

Chief Justice Rehnquist, however, directly pointed to the crux of the issue when it comes to critical mass, and Justice Scalia furthered this inquiry in his interrogation of the law school’s attorney Maureen E. Mahoney:

JUSTICE SCALIA: Is 2 percent a critical mass, Ms. Mahoney?MS. MAHONEY: I don't think so, Your Honor.JUSTICE SCALIA: O.K. 4 percent?MS. MAHONEY: No, Your Honor, what --JUSTICE SCALIA: You have to pick some number, don't you?MS. MAHONEY: Well, actually what --JUSTICE SCALIA: Like 8, is 8 percent?MS. MAHONEY: Now, Your Honor.JUSTICE SCALIA: Now, does it stop being a quota because it's somewhere between 8 and 12, but it is a quota if it's 10? I don't understand that reasoning. Once you use the term critical mass and -- you're -- you're into quota land?MS. MAHONEY: Your Honor, what a quota is under this Court's cases is a fixed number. And there is no fixed number here. The testimony was that it depends on the characteristics of the applicant pool.JUSTICE SCALIA: As long as you say between 8 and 12, you're O.K.? Is that it? If you said 10 it's bad you but between 8 and 12 it's okay, because it's not a fixed number? Is that -- that's what you think the Constitution is? MS. MAHONEY: No, Your Honor, if it was a fixed range that said that it will be a minimum of 8 percent, come hell or high water, no matter what the qualifications of these applicants look like, no matter what it is that the majority applicants could contribute to the benefits of diversity, then certainly that would be a quota, but that is not what occurred here. And in fact the testimony was undisputed, that this was not intended to be a fixed goal.

Pretty brutal grilling, huh? But you see the heart of the matter here, don’t you? When exactly is critical mass achieved??? If we intuitively understand that 1 black student is not enough to bring about any benefits of diversity when the other 2999 students are all Chinese, then how many black people do we need? 10? 200? 500?

But herein lies the danger! As you’ve seen with Bakke and Gratz, the moment you associate race with hard numbers it’s all over. This is why Justice Scalia is attacking Mahoney so relentlessly. He wants to get her to confess that there’s some secret number they’re trying to hit which would instantly render critical mass an unconstitutional quota. Mahoney knows this, which is why she’s parrying those blows so expertly by deliberately and carefully avoiding saying that there’s any strict numerical target when it comes to critical mass, that it’s not just a light switch that magically flips on at a specific percentage because it’s instead something that depends on a variety of factors.

Come on, look at this drama, this cat-and-mouse game of volleys! I’m telling you, Supreme Court cases are as incredibly entertaining as they are educational!

Thus, because there were no definitive numbers associated with critical mass, UMich and every other school was allowed to pursue diversity as a goal in its admissions process, as Justice O’Connor writes in her opinion of the Court:

📜 As part of its goal of “assembling a class that is both exceptionally academically qualified and broadly diverse,” the Law School seeks to “enroll a ‘critical mass’ of minority students.” The Law School's interest is not simply “to assure within its student body some specified percentage of a particular group merely because of its race or ethnic origin.” Bakke, 438 U. S., at 307 (opinion of Powell, J.). That would amount to outright racial balancing, which is patently unconstitutional. Rather, the Law School's concept of critical mass is defined by reference to the educational benefits that diversity is designed to produce.These benefits are substantial. As the District Court emphasized, the Law School's admissions policy promotes “cross-racial understanding,” helps to break down racial stereotypes, and “enables [students] to better understand persons of different races.” These benefits are “important and laudable,” because “classroom discussion is livelier, more spirited, and simply more enlightening and interesting” when the students have “the greatest possible variety of backgrounds.”So okay, the two essential criteria to evaluating whether an affirmative action policy is legal can now be refined to this:

Critical Mass: a certain amount of diversity (no numbers) has proven benefits to everyone

Narrowly Tailored: consider every applicant on an individual basis (NO NUMBERS!)

Now that you’ve gotten this far, check out this video of people from both sides speaking about the case before the court’s decision. It’s good to be able to put faces to names and hear the arguments from their mouths. Plus, you’ll feel really good that you can understand what they’re talking about, even when they mention legal terms like the Equal Protection Clause and Title VI. This is high level stuff that most Americans don’t even understand!

Fisher v. University of Texas (2013) and (2016)

Okay, last one, we’re nearly done. This case itself doesn’t seem very remarkable on the surface: UT automatically accepts the top 10% of high school graduates. This helps with their diversity goal because it ensures that they get a good number of students from schools that are heavily populated by minorities, and this isn’t a problem because they’re not giving any racial bonuses. UT is able to fill 80% of its incoming freshman class this way, and the rest of the spots are basically determined by a combination of academics and other factors, including race.

Abigail Fisher, a white girl who was below the top 10% of her class, claims that she would’ve gotten in if she were given racial preference like minorities were for the non-guaranteed spots.

Abigail Fisher with her attorney Bert Rein talking to reporters outside the Supreme Court on Oct. 10, 2012 (photo by Susan Walsh for AP)

Except with her 3.59 GPA and 1180 SAT score, Fisher wouldn’t have gotten in regardless:

As a result, university officials claim in court filings that even if Fisher received points for her race and every other personal achievement factor, the letter she received in the mail still would have said no.It's true that the university, for whatever reason, offered provisional admission to some students with lower test scores and grades than Fisher. Five of those students were black or Latino. Forty-two were white.Neither Fisher nor Blum mentioned those 42 applicants in interviews. Nor did they acknowledge the 168 black and Latino students with grades as good as or better than Fisher's who were also denied entry into the university that year. Also left unsaid is the fact that Fisher turned down a standard UT offer under which she could have gone to the university her sophomore year if she earned a 3.2 GPA at another Texas university school in her freshman year.

And even then, the Director of Admissions explains how race is considered holistically, much like the way the UMich law school did in Grutter which has already been ruled constitutional:

Race, like any other factor, is by itself never determinative of an admissions decision and like every other factor is never considered in isolation or out of the context of other aspects of the student’s application file. Race is considered as part of the larger holistic review of every applicant regardless of race. No applicant is reviewed separately or differently because of their race or any other factor. An applicant’s race, standing alone, is neither a benefit nor detriment to any applicant. Instead, race provides – like language, whether or not someone is the first in their family to attend college, and family responsibilities – important context in which to evaluate applicants, and is only one aspect of the diversity that the University seeks to attain.

So what’s the deal here? Why is she suing when she already ended up graduating from Louisiana State University? What’s her goal when all she would get from winning the case is a paltry $100 (the total refunded amount of her application fee and housing deposit)? Why would the Supreme Court even bother to hear this case when her name only appears five times in the many, many thousands of words that make up the complaint?

Ah, and here we get to the part that’s actually intriguing: this isn’t about Fisher wanting to get into UT at all. This is about one person’s quest to challenge the entirety of affirmative action, and that person is not a student, not the parent of a student, and not even anyone who has any relation to anyone involved in college admissions.

That person is a former stockbroker named Edward Blum, the man who bankrolled Fisher’s case and several other cases that attempted to challenge affirmative action through a group he made called Project for Fair Representation.

Here’s the video that group made for the Fisher case:

It’s clear what they’re trying to do to, from the piano music to the way Fisher is presented. Knowing everything you do now about the history of affirmative action, I leave it to you to ponder the strength and validity of their arguments.

Fisher ultimately lost, but only narrowly in a 5-4 vote. And now, after Donald Trump appointed three more justices (Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett), the Supreme Court—the same one that overturned Roe v. Wade and ended the federal right to abortion—is far more conservative and far more likely to overturn affirmative action.

Fisher wasn’t Blum’s first attempt. To advance his crusade against laws pertaining to racial preferences, Blum has funded several others as the Project for Fair Representation, including someone who believes that God created Adolf Hitler and the Holocaust and another who believes that the sun revolves around the Earth. Blum likely realized that representing these kinds of people who garner little to no sympathy wasn’t the way to go, so one day he sat down and thought to himself, “Hmm… who can I use to challenge affirmative action who isn’t white but who also doesn’t benefit from those policies?”

Thus, Blum transformed the Project for Fair Representation into the Students for Fair Admissions, also known as the SFFA (yes, that SFFA), and sued Harvard on behalf of the Asian-Americans who didn’t get in.

And so we have come full circle to SFFA v. Harvard (2022). Next month, we’ll show you just how deep this rabbit hole goes. 🪶

MORE ARTICLES FROM